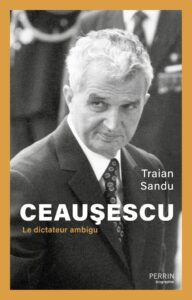

Book release: an examination of Nicolae Ceaușescu’s political career: “The ambiguous dictator”

Professor Traian Sandu, renowned for his insightful history of the Iron Guard (Translator’s Note: The Iron Guard, founded in 1927 by Corneliu Zelea Codreanu, was a Romanian fascist movement and party, notable for its anti-Semitic, anti-communist, anti-capitalist, and anti-democratic ideologies), has recently unveiled, in Paris, a remarkable analysis of Nicolae Ceaușescu’s political trajectory, titled „The ambiguous dictator”. If the adage „a picture is worth a thousand words” holds true, then the book’s cover strikingly exemplifies this, with the depiction of Ceaușescu emanating suspicion, disdain, conceit, and arrogance.

Ceaușescu epitomized the cadre politics of the Romanian Communist Party (PCR). Lacking formal education and barely proficient in the Romanian language, he was characterized by arrogance, zealotry, cunning, and manipulative tactics, leaving an indelible imprint on Romania’s history during, and subsequent to, his reign. In the initial chapters, Traian Sandu delves into Ceaușescu’s pre-leadership career, marked by unswerving loyalty to the PCR and USSR leaders and infused with fanaticism.

His career is marred by heinous acts, including a pivotal role in the forced collectivization leading to 80,000 arrests, and direct accountability for the Vadul Rosca massacre on December 4, 1957, which resulted in nine fatalities and forty-eight injuries.

Leveraging his unassailable hold over the party machinery and the prevailing rifts among the senior communist leaders, Ceaușescu ascended to power in 1965, systematically fortifying his dominion over the party and nation. He meticulously undermined the authority of the PCR’s governing entities while amplifying the political sway of his family and a few personal minions. Ceaușescu adeptly exploited the transgressions of the Communist regime, selectively vindicating some of his victims— not as an act of justice but as a stratagem to cow his perceived adversaries within the party hierarchy.

In his assessment of foreign policy, Traian Sandu labels Ceaușescu an „ambiguous dictator.” This designation seems apt considering his engagements with Richard Nixon and subsequent U.S. presidents, Charles de Gaulle, and other Western leaders; Romania’s acknowledgment of the Federal Republic of Germany; his maintained diplomatic ties with Israel in 1967; condemnation of the USSR’s intervention in Czechoslovakia in 1968; attempts to mediate between China and the USSR, Israel and Arab nations, and the U.S. and Vietnam; and notably, his policy of independence from the Soviet Union.

Traian Sandu offers a precise depiction of Nicolae Ceaușescu’s ‘cultural revolution,’ spearheaded by the reprehensible Dumitru Popescu-Dumnezeu (Translator’s Note: a.k.a. Dumitru Popescu-God; The nickname „God” for Popescu likely originated from his significant influence in implementing political censorship and his role in constructing Nicolae Ceausescu’s cult of personality during the 1970s. He was a crucial figure in socialist culture and education, suggesting that his views and decisions were paramount and unassailable in these domains). This revolution was an amalgamation of neo-Stalinism and fascistic ultra-nationalism. Predominant orchestrators of this cultural obliteration propagated in the name of ideological purity, included demagogic advocates like Adrian Paunescu, Eugen Barbu, and Corneliu Vadim Tudor, who are prominently featured in the volume. The Ceaușescu regime resurrected several legionary and communist ideologists from within and outside the country to blur the lines between communism and fascism in defining the regime’s ideology through their writings and actions.

For Romanians, Ceaușescu’s unassailable authority signified anguish and affliction. The reign of the Securitate’s terror, indiscriminate arrests, the prohibition on abortions, forced industrialization, the irrational settlement of foreign debts, an undue emphasis on exports over domestic consumption, a substantial reduction in domestic energy consumption, scarcity of food, restrictions on private vehicles, and a substantial dip in the populace’s purchasing power plunged the nation into despair and eventual rebellion.

The volume concludes with a chapter titled ‘The posthumous revenge of Ceaușescu,’ hinting at a tragic connotation for Romania’s post-communist history and present condition. Recent surveys exhibit a recalibration of Nicolae Ceaușescu and Ion Antonescu’s perception amongst Romanians, with rising approval ratings for both dictators nearing 50%.

The collective forgetfulness of Romanian society, along with the extremist elements in post-communist Romania, particularly parties like PRM and PSM led by Ceaușescu’s court poets – Corneliu Vadim Tudor and Adrian Păunescu, have programmatically striven for the dictators’ rehabilitation. These parties, accounting for 15-20% of the electorate, were fiercely anti-Semitic and Holocaust-denying entities.

To bolster his party’s international credibility, Tudor, guided by paid Israeli advisers who disregarded the stance of the Yad Vashem Institute and the Federation of Jewish Communities in Romania, pledged in 2003 to abandon anti-Semitism and Holocaust denial, even proposing a monument in memory of Yitzhak Rabin in Brasov. Predictably, Tudor’s pledges remained unfulfilled as he perpetuated his anti-Semitic stance until his demise.

The decline of PRM did not signify the disappearance of its audience. Political analysts concur that contemporary extremist entities have appropriated PRM’s electorate and much of its rhetoric, including the glorification of war criminals, anti-Semitism, Holocaust denial, and anti-EU propaganda with pro-Russian inclinations. Current extremist entities in Romania are thus perpetuating Ceaușescu’s post-1989 legacy, revitalized by PRM and its allies, invoking their aggressive, intimidating, impertinent, and hooliganistic strategies in public life, posing unsettling prospects for Romania’s political trajectory.

NOTE: This text was written by the author in a private capacity and in no way implies the responsibility of institutions with which he is affiliated.

Translated by Ovidiu Harfas

Urmărește mai jos producțiile video ale G4Media:

Donează lunar pentru susținerea proiectului G4Media

Donează suma dorită pentru susținerea proiectului G4Media

CONT LEI: RO89RZBR0000060019874867

Deschis la Raiffeisen Bank

1 comentariu