Transdisciplinary research for the reactive control and proactive risk assessment of zoonotic epidemics – Virgil Iordache

Introduction

Urmărește cele mai noi producții video G4Media

- articolul continuă mai jos -

About 13 years ago experts in virology have written in one of the most important microbiological scientific journals the following recommendation: “The presence of a large reservoir of SARS-CoV-like viruses in horseshoe bats, together with the culture of eating exotic mammals in southern China, is a time bomb. The possibility of the reemergence of SARS and other novel viruses from animals or laboratories and therefore the need for preparedness should not be ignored” (Cheng et al. 2007). Other Chinese scientists make today an explicit link between the current pandemics and unexplained pneumonia patients in the Wuhan seafood market (Xu et al. 2020). Such statements, and a lot of other sound scientific knowledge have been ignored by the public, the decision makers and the states, leading to losses of lives and an estimated global economic cost, at this moment, of about 5 trillions of dollars needed for recovery (G20 estimation), not to mention the human lives.

A problem to be solved after we get out of the current public health situation is how to improve the rationality of decision making with respect to zoonotic epidemics, how to take into account all relevant bodies of knowledge to prevent such crisis, and to better manage them when the occur.

In this text I will provide a potential research framework and a syntheses of relevant scientific information. For our scientific community and general public there are three aspects which will be probably perceived as novel (although there is nothing novel from international perspective):

- Nature and biodiversity can be not only good, but also bad, there are so called “ecosystem disservices”, of which zoonotic epidemics are an example. These disservices depend to some extent on how we manage the natural capital. The “good nature” image socially constructed after the environmental crisis has to be adjusted;

- Effective prevention of epidemics can be performed only by a multidisciplinary monitoring and research.

- Efficient reactive management (control) of epidemics can be done only by integrated assessment of public health, economic social and defense risks, there is not one single most important institution in this equation.

1 Potential research framework

The scheme below depicts a potential complex long-term research project involving scientists, governance institutions and other stakeholders, able to support decisions about zoonotic epidemics.

Figure 1 Overall scheme of an integrated projects with two clusters of subprojects: one dedicated to proactive prevention, and one to reactive management (control). Both of them need strong knowledge and data about ecological and human processes relevant for the dispersion and its effects at individual (organismal) and population (social) scale.

Cluster A it’s a matter of management science, governance, political science, economy, institutional analysis and development. I will not develop it, as it is outside my direct field of expertise. Cluster be is a matter of integrated long-term research and monitoring, a field similar with what is envisaged in sustainability science. Actually, while the research in sustainability science is traditionally focused on the “good nature”, here something accounting for the management of one kind of ecosystem disservices should be developed.

Potential objectives in cluster B (syntheses of relevant scientific knowledge in the next part of this text):

- Mapping hotspots of viral sharing by birds and mammals in Romania, in the frame of a process based accounting of ecosystem disservices at national scale

- Modeling the effects of habitat fragmentation and climate change on the dispersion of relevant vector species at regional and macro-regional scale

- Accounting for the management practices responsible for the increasing risk of viruses’ transfer to human populations.

- Construction of a data and knowledge transfer interface from environment and sustainability studies towards the scientific community of epidemiologist.

A full design of the research program can be done by standard project management techniques (brainstorming with inter-disciplinary teams, etc).

2 Short syntheses of relevant scientific information

As the literature is huge in each direction here I provide only a small sample of articles. In a project management framework full critical analysis of the literature in each sub-field will be a must before any decisions on the research design.

2.1. Epidemiology and causal complexity

Oosterbroek et al. (2016) “mention the linear, reductionist approaches of epidemiology and public health research in the second half of the 20th century, focusing on proximate cause-and-effect relationships.” They state that “by training, epidemiologists and public health researchers are less accustomed to studying causes within a systems context or addressing long time frames. Most health scientists will therefore not be familiar with the complex quantitative modeling approaches that are developed by ecosystem scientists”.

Nature can be both good and bad for human health, by different processes: “The relationship between biodiversity and infectious diseases is not straightforward; disease dynamics are complex and dependent on the system, which includes the infectious agents, their targets and hosts, their vectors, the environment (natural as well as technological and sociocultural), and the mechanisms and interactions connecting them” (Keune and Asmuth 2018).

“The need of prospective scenarios of health that are embedded in the socio-ecosystems is crucial“: “Integrating the various dimensions of complexity thanks to disciplines such as ecology and environmental sciences, health sciences, policies and law, we analyze retrospectively, and comparatively infectious diseases’ dynamics associated to policies, land use and biodiversity changes.” (Lajaunie et al. 2019).

2.2 Ecosystem disservices and the role of biodiversity in zoonotic epidemics

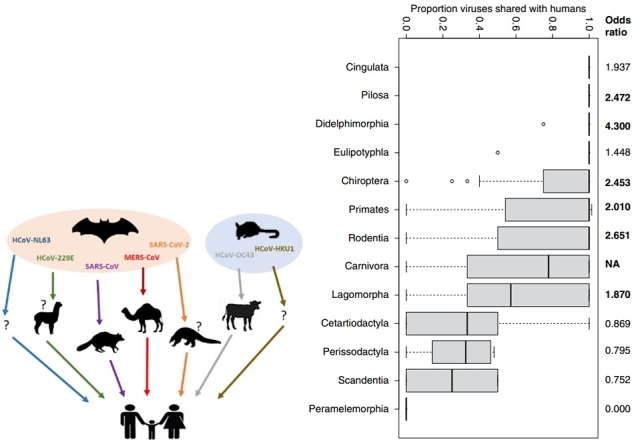

“Between 10,000 and 600,000 species of mammal virus are estimated to have the potential to spread in human populations, but the vast majority are currently circulating in wildlife, largely undescribed and undetected by disease outbreak surveillance.” (Carlson et al. 2020). “Systematic effects of biodiversity change on infectious disease could have enormous economic, public health, and conservation implications. As examples, at least 60% of all human disease agents are zoonotic in origin” (Young et al. 2016, and figure 2).

Figure 2 Left Animal hosts of HCoVs from their natural hosts (bats or rodents) to the intermediate hosts (camelids, civets, dromedary camels, pangolins or bovines), and eventually to the human population (Ye et al. 2020). Right Boxplots based on species‐level data of proportion of viruses for several species in an order that are zoonotic (Olival et al. 2015).

Birds can also be “carriers of other organisms or their propagules” spreading “disease to humans and poultry” and increasing the “incidence of human and livestock disease and death”; there is a moderately negative valuation of birds by society, at a global scale of relevance (Buij et al. 2017).

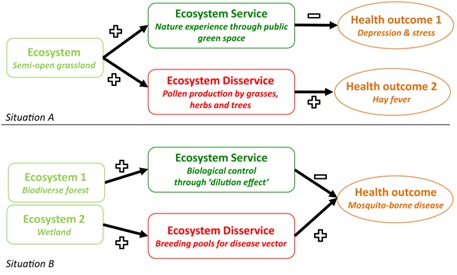

Disservices of nature like zoonotic diseases are a kind of ecosystem disservices. Despite the large scientific literature representations of ecosystem disservices are still marginal in the public opinion (Lyitimaki 2014), because of the past environmental crisis which led to an exaggerated shift towards completely positive image of the nature (socially stabilized then by political ideologies such as ecologism). There is an increasing trend for the integration of ecosystem services and disservices provided by all parts of biodiversity (for the case of plants see for instance Vaz et al. 2017). An example is provided in figure 3.

Figure 3 Two examples illustrating the complexity of ecosystem – health relationships when considering both ecosystem services and disservices (Oosterbroek et al. 2016)

2.3 Human action on nature has consequences on zoonotic diseases

“Changing climate and land use drive geographic range shifts in wildlife, producing novel species assemblages and opportunities for viral sharing between previously isolated species. In some cases, this will inevitably facilitate spillover into humans — a possible mechanistic link between global environmental change and emerging zoonotic disease” (Carlson et al. 2020). Global effects on species diversity may lead to bottom up effects on emerging diseases (figure 4). The fragmentation of natural habitats is hypothetically related to infectious disease emergence (figure 4; the real situation have to be checked in the case of each socio-ecological system).

Donează lunar pentru susținerea proiectului G4Media

Donează suma dorită pentru susținerea proiectului G4Media

CONT LEI: RO89RZBR0000060019874867

Deschis la Raiffeisen Bank

© 2025 G4Media.ro - Toate drepturile rezervate

Acest site foloseşte cookie-uri.

Website găzduit de Presslabs.